Responsive, Sensitive and Reflective

Parenting. The Value of Parental Support

in Merseyside; A qualitative study.

‘

Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the

University of Liverpool for the degree of Master of Philosophy

By Miss Clare Katherine Oliver’

Acknowledgements

I would firstly like to thank my primary supervisor Dr Melissa Gladstone. Thank you for

providing me with your thoughts and inspiration to complete this project. I am truly grateful

for the opportunity you have given me to complete this intercalated year and support

throughout the year. I would also like to thank my secondary supervisors, Dr David

Taylor-Robinson and Dr Lisa Marsland. Thank you David for your insights into public health and

Lisa for inspiring me to further explore the concept of reflective parenting, opening my eyes

to this new theory of child development. I have enjoyed our meetings this year.

I would also like to thank Vicky Fallon who gave up so much of her time to help me.

I would like to thank the University of Liverpool for providing the funding for this study as

well as the opportunity to take an intercalated year and also the staff at Alder Hey who

guided me through my NHS ethical application.

For the support and advice with the project as well as encouraging the other Health Visitors

to listen to me and assist with recruitment I would like to thank Steph Griffiths.

I would like to offer my thanks to Debi McAndrew and all the children’s centre managers

across Merseyside for being so welcoming, especially during a time when your jobs and the

future of the centres was not secure. Jane for organising the focus group discussion and

Leanne, Mo and other staff at the children’s centres who allowed me to sit in on their

sessions and promote the project.

My family, not only have you provided the ongoing finical support to allow me this

opportunity to take a year out of my medical degree, but you have also provided constant

emotional support and advice throughout the year. Zach, thank you for all those early

morning starts and late nights picking me up from the station and all your support throughout

the year. Charles, thank you for all your efforts, proof reading and keeping me calm as the

deadline approached.

Finally and most importantly, my thanks must go to the parents of Liverpool. I was

privileged to be given such insight into your lives and grateful to every participant for taking

the time to speak to me. The experience has been invaluable and you have taught me the

importance of communication and empathy, which I will take this with me throughout my

medical career. My time spent talking to you all has given me a far better understanding of

Responsive, Sensitive and Reflective Parenting. The Value of Parental Support in Merseyside; A qualitative study.

Background: Throughout the world it is thought that over 200 million children are not reaching their full developmental potential. In the UK it has been estimated that just under half (48%) of children are not reaching a level of ‘good development’ by the age of 5 years. This is particularly the case in children from inner-city areas such as Liverpool, Merseyside. Research has shown the importance of responsive, sensitive and reflective caregiving in improving a child’s development and research has demonstrated the need to support parents with this. The UK government provides parents with support with their parenting via various services and policies including Health Visitors, Midwives and children’s centres. It is not clear however, which services parents in Merseyside are accessing and what support they value. In October 2015, the control of funding for all children’s services will be passed to local authorities and children’s centres’ funding is under a 2 year period of review and so it is a crucial time to question what, how and why parents use the support networks and services they do. By doing so we can better cater the services to the needs of the parents and hopefully improve childhood development in Liverpool, Merseyside.

Aim: To understand how caregivers from different backgrounds in Merseyside know and learn to be responsive, sensitive and reflective to their babies. Where they go to for support and what services they value.

Methods: Qualitative semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions were chosen as the main research methods for gathering data. The eligibility criteria included all English speaking caregivers of children aged less than 2 years old. Interviews and focus group discussions were audio recorded and transcribed. Thematic content analysis was used to identify key themes in relation to the study aims.

Results: 22 parents were interviewed, 21 mothers and 1 father. One focus group discussion was held with 5 participants. Parents spoke of requiring additional support when their child was ill, due to their child’s sleep routine, to overcome isolation and as single parents. Parents used a variety of services and people to support them with their responsive, sensitive and reflective caregiving. This included their partners, family members, other mothers, children’s centres, Health Visitors, BAMBIs breastfeeding support and the internet. It emerged that ‘relationships’, ‘professionalism’ and ‘experience’ were crucial factors in the support valued by parents. This included forming a positive relationship with health care professionals and utilising the expert knowledge of staff running a service. It also included the ability to discuss their child’s development with other mothers as well as comparing experiences.

Conclusions: Services which support parents in the early years of their babies’ lives should consider the importance of the relationships they form with their parents, especially when delivering advice. Health Visitor leaders should consider deploying the same Health Visitors at weigh-in sessions each week to improve the relationship with parents in the hope that parents will make greater use of this service to support them in their caregiving. Children’s centres were a vital support service for parents interviewed as the staff had formed positive relationships with parents, they were professionally trained and centres provided an

“

It takes a village to raise a child”

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements ... 0

Abstract ... 3

List of Figures ... 12

List of Tables ... 13

List of Abbreviations ... 14

Chapter One: Childhood Development: Introduction and Background to the Study ... 15

1.1. The Importance of Childhood Development ... 17

1.2. A Global Focus on Childhood Development: The current situation ... 18

1.3. Current Gaps in the Evidence ... 19

1.4. How to Support Parents in a Local Context ... 20

1.5. Study Aim ... 21

1.6. Introduction to the Study ... 21

Chapter Two: Theories of Childhood Development Literature Review ... 23

2.1. Theories of Childhood Development ... 27

2.1.1. The importance of Attachment in Childhood Development ... 28

2.1.2. Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory ... 31

2.1.3. Social Models of Childhood Development ... 33

2.2. Parental Interventions and the Need to Support Parents; The Evidence .... 35

2.2.1. The Importance of Sensitive, Responsive and Reflective Care ... 36

2.2.2. Barriers to a Parent’s Natural Caregiving Abilities ... 41

2.2.3. The Benefits of Parenting Interventions ... 43

2.3.1. Midwives ... 48

2.3.2. Health Visitors ... 48

2.3.3. Sure Start Children’s Centres ... 50

2.3.4. The Family Nurse Partnership... 52

2.3.5. National Academy for Parenting Research ... 53

2.4. The Value of Support to Parents ... 55

2.4.1. Parental Views on Government Services ... 55

2.4.2. Why Parents Engage in Support Services ... 57

2.4.3. The Type of Support Parents’ Value ... 57

2.5. Conclusions ... 59

Chapter Three: Qualitative Methodology... 61

3.1. Qualitative Methodology, Background and Reasons for its Use ... 64

3.2. Data Collection Methods within Qualitative Research ... 65

3.2.1. Questionnaires ... 66

3.2.2. Observational Techniques ... 66

3.2.3. Interview Techniques ... 67

3.2.4. Focus Group Discussions ... 68

3.2.5. Topic Guides ... 70

3.3. Sampling in Qualitative Research ... 72

3.3.1. Purposive Sampling ... 73

3.4. Sample Sizes in Qualitative Research... 73

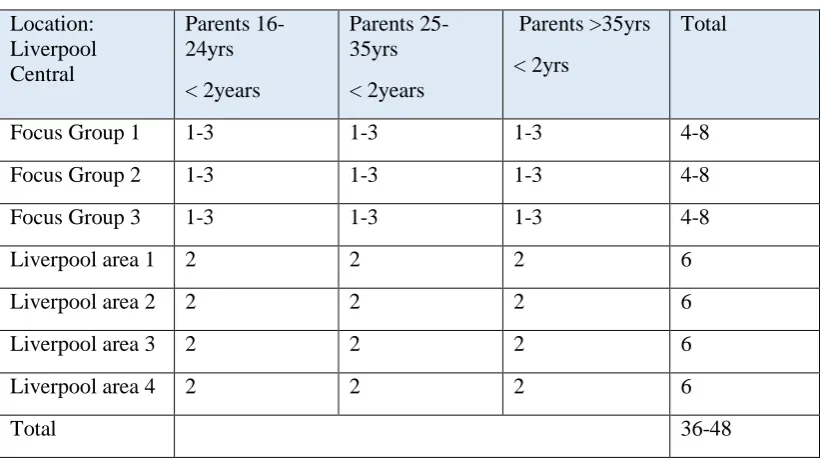

3.4.1. Sampling Matrix ... 74

3.5. Population and Selection Criteria in Qualitative Research ... 75

3.6. Recruitment in Qualitative Research ... 76

3.7. Recording and Transcription of Qualitative Data ... 76

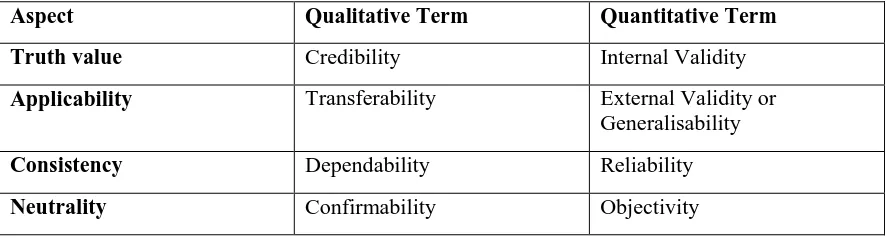

3.9. Ensuring Quality within Qualitative Research ... 79

3.9.1. Stakeholder Consultation Group ... 81

3.9.2. The Role of the Researcher ... 82

Chapter Four: Study Methodology ... 85

4.1. Background ... 87

4.2. Aim ... 88

4.3. Objectives ... 89

4.4. Study Design ... 89

4.5. Sponsorship and Ethical Approval ... 89

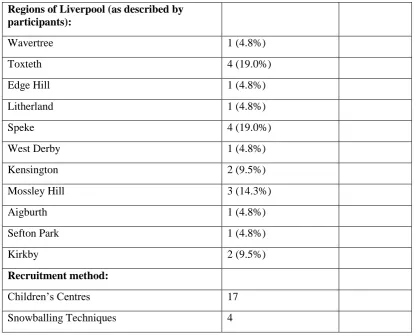

4.6. Setting ... 89

4.7. Experimental Design ... 90

4.7.1. Sampling Criteria ... 90

4.7.2. Sample Size ... 90

4.8. Recruitment and Selection Procedure ... 91

4.8.1. Interview Recruitment ... 91

4.8.2. Focus Group Discussion Recruitment ... 92

4.8.3. Information Leaflets ... 92

4.8.4. Consent Forms ... 92

4.9. Semi – Structured Interviews ... 93

4.9.1. Semi-structured Interview Topic Guide ... 93

4.10. Focus Group Discussions ... 95

4.10.1. Focus Group Discussion Topic Guide ... 95

4.11. Data Analysis ... 96

Chapter Five Results ... 99

5.2. Study Period ... 101

5.3. Recruitment ... 101

5.4. Participants Included in the Study ... 102

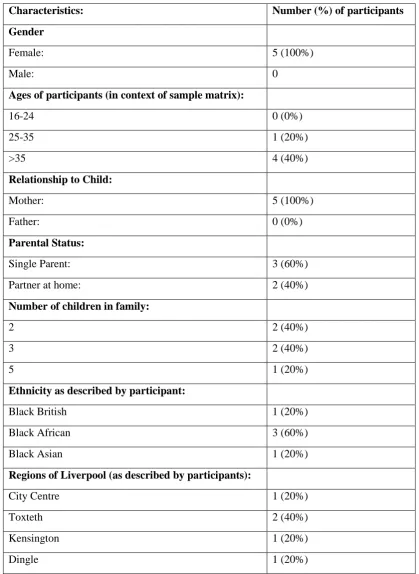

5.4.1. Interview Participants ... 103

5.4.2. Focus Group Participants ... 105

5.5. Data Collection ... 107

5.6. Themes and Results of the Study ... 108

5.6.1. The Parent- Child Relationship ... 109

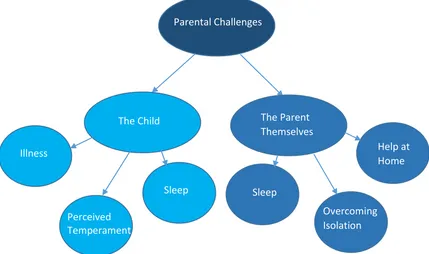

5.6.2. Challenges to Being a Responsive, Sensitive and Reflective Parent ... 111

5.6.3. How Parents are Being Supported in Relation to Responsive, Sensitive and Reflective Caregiving ... 117

5.6.4. Why Parents Value the Support They Receive in Relation to Their Responsive, Sensitive and Reflective Care ... 130

5.6.5. How Satisfied Parents are with the Support They Receive in Relation to Their Responsive, Sensitive and Reflective Care ... 137

Chapter Six Discussion and Conclusions ... 139

6.1. Summary of Findings ... 141

6.2. Discussion of Findings ... 142

6.3. Limitations and Strengths of the Study... 157

6.4. Implications for Clinical Practice ... 161

6.5. Directions for Future Research ... 166

6.6. Summary of Thesis ... 167

References ...171

Appendix...183

Appendix B: Information for Participants (Final Versions)...188

Appendix C: Courses Attended to Support the MPhil...199

Appendix D: Participants’ Demographics...200

List of Figures

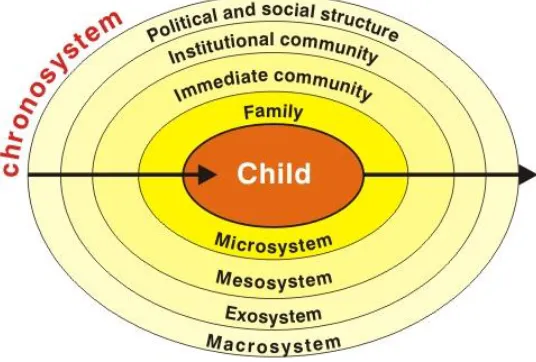

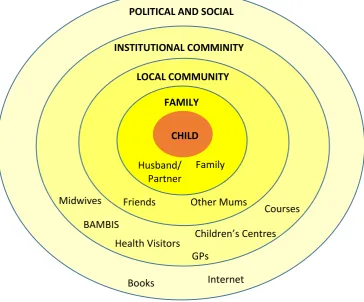

Figure 2.1: Halpern R’s interpretation of Bronfenbrenner’s theory of child

development………...34

Figure 5.1: Map of participant recruitment across Merseyside………...104

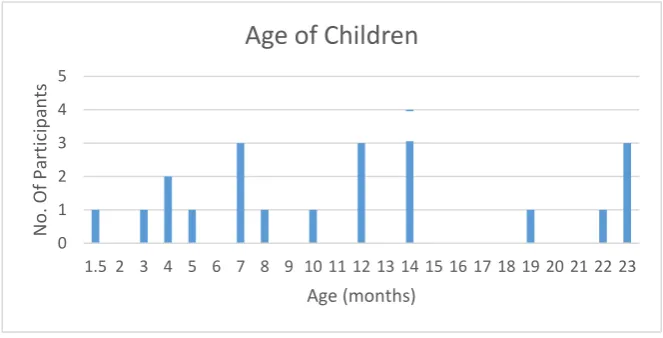

Figure 5.2: Graph of interview participants’ ages. ………...105

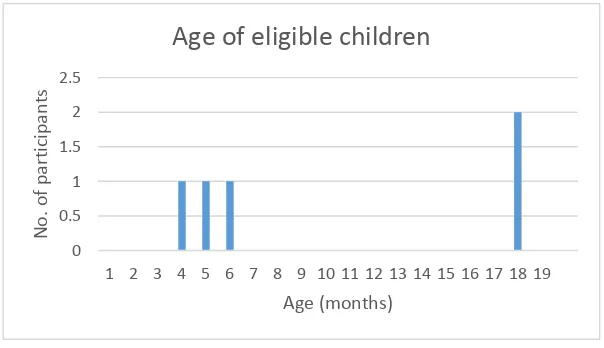

Figure 5.3: Graph of interview participants’ eligible children’s ages…………...105

Figure 5.4: Graph of focus group discussion participants’ ages………...…107

Figure 5.5: Graph of focus group discussion participants’ eligible children’s ages………...…107

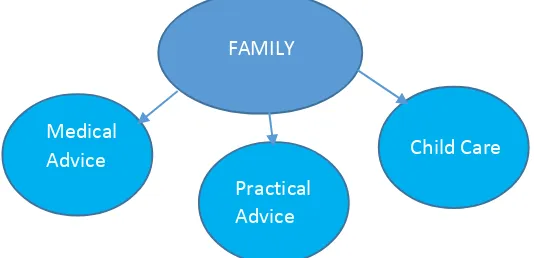

Figure 5.6: Diagram showing the parental challenges reported by participants…111 Figure 5.7: Diagram showing where parents went for advice and support…...118

Figure 5.8: Diagram showing how parents were supported by their husband / partner………...…118

Figure 5.9: Diagram showing how parents were supported by their family…...120

Figure 5.10: Diagram showing how parents were supported by their friends / other mothers………...…122

Figure 5.11: Diagram showing how parents were supported by the institutional community………...…124

Figure 5.12: Diagram showing how parents were supported by the political and social culture………..…128

List of Tables

Table 1: Lincoln and Guba’s comparison of qualitative and quantitative quality of research terms ………...…79

Table 2: Proposed sampling matrix………...…91

Table 3: Table showing the demographics of interview participants ……….103

Table 4: Table showing the demographics of the focus group discussion

participants………....…106

List of Abbreviations

AAI Adult Attachment Interview FNP Family Nurse Partnership

NAPR National Academy for Parenting Research NHS National Health Service

PEEP Peers Early Educational Partnership PDI Parent Development Interview RF Scale

SIDS

Reflective Functioning Scale Sudden Infant Death Syndrome

UK United Kingdom

Chapter One

Childhood Development: Introduction and

‘Childhood development’ pertains to the period from birth to adolescence during which critical biological, physical and emotional changes occur to a person as their brain and body grow to take on their adult form. From birth to five years old children make rapid gains in their speech and language, gross and fine motor, communication and independence skills.(1) The areas of development are thus often measured in the following four domains; gross motor, vision and fine motor, hearing speech and language and the final domain, social emotional / behavioural. Research has shown that developmental delay in any or all of these domains can occur due to a number of factors, both genetic and environmental.(1) One of the most important major factors is the relationship a child forms with their primary caregiver. This has been well documented as having a significant impact on a child’s overall development.

1.1. The Importance of Childhood Development

Childhood development is currently of major interest to health and social policy makers and is being placed high on the agenda for the new sustainable development goals, 2015.(2) Evidence suggests that over 200 million children globally may not be reaching their full developmental potential, resulting in adverse consequences in their adult lives.(3) Children not reaching their full developmental potential is not just limited to children growing up in more economically deprived countries, but is also a key issue of concern in many more privileged settings throughout the world.

consequences of poor development. It is therefore crucial that every child is given the best possible start in life.(5)

In the United Kingdom [UK] many children are not reaching their developmental potential. A report from the Department of Education in 2013 stated that only just over half of 5 year old children (52%) were reaching the government defined level of ‘good development’ during their pre-school developmental checks.(7) Children are assessed using the early learning goals covering seven areas of learning including, communication and language, physical development, personal, social and emotional development, literacy, mathematics, understanding the world and expressive arts and design.(7) For children growing up in more disadvantaged areas of the country, where there are high levels of child poverty the figures reaching a ‘good level’ of development is much lower.(7) In Liverpool, Merseyside, 33% of children are growing up in poverty and the overall health and wellbeing of children, including factors such as immunisation uptake, hospital admissions and overall child development amongst other factors is worse than the national average.(8) In 2014 one report showed that only 50% of children in Liverpool were reaching the government’s level of ‘good development’.(8) With a high population of children within the city, (5,942 live births in 2012) this means that thousands of children are not be reaching their full developmental potential in Merseyside.(8) There is therefore real concern that more should be done to support the development of the children of Liverpool.

1.2. A Global Focus on Childhood Development: The current situation

From a global perspective, Margaret Chan, head of The W.H.O has recently

published a letter making it very clear how inadequate, disrupted and negligent care, can have adverse consequences for childhood development. Professor Chan stresses that as a global community we need to be developing policies that can impact earlier in a child’s life to prevent these poor outcomes. (4) Throughout the world the

Within the UK there, has been a clear focus on utilising evidence based initiatives to provide more support for parents. These initiatives have been mixed and varied in their approach and have come from a range of health, social welfare and education settings, all with an aim of ensuring that children are given the best possible start in life regardless of their social background.(11) The developmental potential of a child in the UK is influenced by both their parents’ caregiving, which is in turn influenced by the support their parents receive from their family, friends, local community and the health, education and social care services provided locally.

1.3. Current Gaps in the Evidence

Multiple research studies have demonstrated how responsive and sensitive caregiving is an important factor in a child’s development.

The seminal work of Bowlby and his ‘Attachment Theory’ in the 1950s first

demonstrated the critical importance of the early bond between mother and child.(12) This work led on to the development of the concepts of sensitive and responsive parenting. Bowlby worked along-side researcher Mary Ainsworth who developed a tool to measure Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, known as ‘The Strange Situation’.(13) She concluded that children will develop secure attachments with caregivers who are sensitive and who respond to them, naming the theory the ‘sensitivity-responsivity theory of attachment’.(4,13)

Sensitive and responsive parenting has continued to be a widely researched area of child development and is the basis of many successful parenting interventions.(14) In more recent years, researchers have moved a step further and explored newer

concepts such as that of Fonagy, who has developed the theory of ‘Reflective

Parenting’ and having the ability to hold your child’s thoughts and feelings in mind. This new concept, although not as well established as that of sensitivity and

child development, any more than approaches relating to promoting responsive and sensitive caregiving.

1.4. How to Support Parents in a Local Context

Since the introduction of the ‘Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children’ in 1883 the need for the government to support children and their development in the UK has long been recognised and supported through various Acts of Parliament and government policies. This includes a number of National Health Service [NHS] as well as local authority delivered services available to support parents. The most recent government policy which encompasses all aspects of early childhood is the 2010-2015 policy on Children’s Health, developed by the 2010-2015 coalition government.(15) This document includes policies directed at supporting parents and their child’s development in the first 1001 days of life, from conception to two years of age. The policy outlines actions that should be taken to ‘help families to have the best start in life’ as well as the services and support that should be available to all UK families regardless of their social or economic background.(15)

From October 2015 local authorities will take over responsibility from NHS England for the delivery of a range of services for children and parents from zero to 5 years old. It is stated within this policy on Children’s Health that local authorities will be expected to understand the needs of their local communities’ best and to target their services accordingly.(15)

national average.(8) In this setting, optimal support for children in the early years could make a real difference and help improve early childhood developmental potential and thus improve population health.

1.5. Study Aim

The aim of this thesis is to better understand how caregivers from different

backgrounds in Merseyside know and learn to be responsive and reflective to their babies, where they go to for advice and support with their parenting and which services they value.

It is hoped that by doing so I can provide timely evidence for those responsible for children’s services in Merseyside as well as the local authority about the needs and wants of the parents of Merseyside at a time when making better informed decisions about the provision of children’s services and improving childhood development is high on the political agenda. By providing evidence to the local authority, I hope that this in turn will allow the local authority to target their service provisions more effectively and begin to improve the developmental outcomes of the children of Merseyside. It will also give more of an insight into the types of services parents’ value where they turn to for support with their parenting.

1.6. Introduction to the Study

Following the brief introduction in this chapter to some of the key concepts

considered in this thesis, I move on to a more in depth consideration of the literature.

currently be supported as outlined in current UK government policy. I conclude chapter two by evaluating the evidence, exploring the extent to which parents actually value support with parenting. Following this, I will outline the aims and objectives of the study in more detail.

Chapter Three, Qualitative Methodology, outlines the general qualitative methods used in my thesis, along with the justification for using these research methods.

Chapter Four, which outlines the study, presents the specific methods and study protocol used in my qualitative study

In Chapter Five, Results, presents the results of my study.

Chapter Two

Theories of Childhood Development and

In this chapter I provide an overview of key literature surrounding the importance parenting has on child development. This will be achieved by discussing important theories behind child development, both historically and in terms of the more modern day theories such as ‘Reflective Parenting’. I will then explore the research

surrounding how demonstrating sensitive, responsive and reflective care can impact upon a child’s development. From this I will look at the evidence which questions if parents have a natural ability to demonstrate these traits and why they may need support with their caregiving. Finally I will evaluate the current evidence which supports the use of parental interventions.

In the next section of the review I will continue by outlining the services which should be available to support all parents within the UK and Merseyside. The final section will then review the evidence exploring the value of such support to parents.

Throughout the literature review, I will focus on literature relating to children aged 0-2 years primarily, as well as the ‘universal parent’. The age range of 0-2 years has been chosen since this is the most critical period in a child’s development. The ‘universal parent’ concept embraces ‘all parents’, with a focus on the general needs of parents in the community as opposed to those who may require more targeted support.

When embarking upon this literature review I conducted three main database searches, in order to establish how parenting can effect child development. This included looking specifically at responsive and sensitive parenting, reflective parenting and the role of parental interventions.

Firstly when conducting this review I explored the literature surrounding sensitive and responsive parenting as this is a well-established theory of childhood

produced a more varied result. Following title and abstract reviews of these results, 3 studies were found to be of relevance to my work and were consequently reviewed. I also used the work of The W.H.O., searching their databases for their own literature reviews on responsive and sensitive parenting and reviewed the citations within their work to explore further evidence relating to this parenting concept.

To establish the evidence to support reflective parenting a literature search was carried out in November 2014 using the keywords ‘reflective’ AND ‘parenting’. The most results were found using the database ‘Scopus’ which gave 109 publications. Reviewing the titles it was clear that not all publications were looking specifically at reflective parenting and further searches were commenced by adding the term

‘reflective functioning’ to ensure these results were specific to Fonagy’s definition of reflective parenting. This reduced the results to 51 results and abstracts were

reviewed in more detail for their inclusion in the review.

To review the importance and effects of parenting interventions in the UK, the keywords ‘parenting’ AND ‘interventions’ were searched in December 2014. The most results produced were using the database ‘Ovid SP’ which gave 174 results. It was clear that the majority of these publications were based upon interventions which were targeted to a specific cohort of parents or children and did not look at the general picture of ‘universal parents’. Therefore the internet search engine ‘Goggle’ was used to establish what universal parenting interventions are available in the UK and more specifically in Merseyside. From this the evidence to support the use of each intervention or support service could then be reviewed. From these searches I discovered the National Association of Parenting Research’s database of parenting interventions and for each intervention recommended, a full literature search was conducted by myself using the intervention title as the keyword in order to fully establish the evidence base of the literature available to support the use of each intervention. A general internet search also led me to establish which specific resources the government provides to support parents of children less than 2 years old in the UK.

these services to parents using keywords such as ‘experience’, ‘value’ and ‘opinions’ during my searches.

2.1. Theories of Childhood Development

The first environment with which a child interacts, is the environment provided by their family. The role of the primary caregiver and immediate family therefore is to produce a stable environment and to provide the child with stimulation, support and nurturance so that the child can reach their full potential.(16) For the past 60 years there has been a myriad of theories developed to explore and explain how this environment can influence a child’s development. Psychologists and clinical practitioners have developed these theories over many years and attempt to explore and understand how these environmental, familial and social factors, influence a child’s development from birth and throughout the early childhood period. The most influential have however focused on the importance of the child – caregiver

relationship and these have in turn been used as the basis for many parental interventions and programmes across the UK.(17)

2.1.1. The importance of Attachment in Childhood Development

John Bowlby, Attachment Theory. 1951

Since 1951 when John Bowlby and his team, with the support of the W.H.O, explored the impact of the separation of children from their families during the evacuations of World War II, ‘Attachment Theory’ has a been a widely recognised theory of childhood development.(12) Bowlby himself believed in a concept known as ‘monotrophy’ in which a child would form an attachment to just one particular individual, the primary caregiver.(12) He believed that there was a critical period in the first two and a half years of life in which a child would form this attachment. Through his work, Bowlby emphasised that this attachment was crucial for a child’s survival and overall healthy development.(18,19) Despite some early criticism of this work relating to the assumed importance of the biological mother’s role, Bowlby’s theory became the best supported theory of childhood development at the time.(4,12) Today, the ‘Attachment Theory’ is still recognised as the foundation to many

subsequent theories of child development which focus on the importance of the child-parental relationship.(4)

Mary Ainsworth: Strange Situation

The ‘Sensitivity- Responsivity Theory of Attachment’ was developed by one of Bowlby’s collaborators, Mary Ainsworth. She had worked along-side Bowlby, and during work in Uganda she completed observational studies of mothers using the tool she developed to measure Bowlby’s attachment theory, ‘The Strange Situation’.(13)

Securely Attached: This is when a child will explore freely when the mother is present in the room. They will engage with the strangers if their mother is in the room, but not if their mother has left. They will be upset on their mother’s departure and happy to see them upon return.

Anxious-Avoidant (insecure attachment); A child will avoid or ignore their caregiver. Little emotion is shown when the caregiver departs or returns and the caregiver will be treated in a similar way to the strangers. They may run away from their caregiver and fail to cling to them when picked up.

This style of attachment forms from a disengaged care-giving style where the child’s needs are not readily met.

Anxious-Ambivalent (insecure attachment); A child is anxious of

exploration and strangers regardless of the caregiver being present or not. Upon the caregivers departure the child will be distressed. Upon their return they will be ambivalent, remaining close to the caregiver but resentful. They may hit out at their caregiver or fail to cling to them when picked up.

This style of attachment occurs when a caregiver is engaged with the child but on their terms only. The child’s needs will be ignored until the caregiver has completed another task.

Disorganised Attachment; The child will show disorganised and confused reactions to their caregiver leaving and entering the room. Some show rocking to and fro and repeatedly hitting themselves.

This style of attachment can occur due to a severe loss or trauma felt by the mother around the birth period causing them to become severely depressed. As a result of this work, Ainsworth concluded that children will develop secure attachments with caregivers who are sensitive and respond to them, calling it the ‘sensitivity-responsivity theory of attachment’.(4,13) Sensitive, responsive caregiving continues to be the basis of many parental interventions today.

towards a person when separated (listening for their voice or noises) showed a secure attachment.(20) When defining attachment, theorists describe how the strength and security of an attachment can vary. Strength refers to the intensity of the attachment through behaviours, as demonstrated by Ainsworth’s strange situation. Security refers to the confidence a child has in the caregiver to be there when needed.(20) In 1968 Schaffer followed 60 infants over an 18 month period in an attempt to measure the ages at which a child should be forming this ‘secure attachment’ as described by Ainsworth. Schaffer described three crucial stages in the social development of an infant following his research, which were vital in allowing the child to form an attachment; (21)

6 weeks following birth; The infant is attracted to other human beings rather than inanimate features in the environment.

3 months following birth; The infant begins to distinguish between different people. The primary caregiver is recognised as ‘familiar’ whereas other are not.

6-7 months following birth; The infant forms their lasting, emotional and meaningful attachment with certain individuals with whom attention is sought.

Sensitive and Responsive Caregiving:

nurturance, stability, predictability and contingent responsiveness.”(23) Over the past 20 years this continuing consensus as to what truly defines sensitive and responsive parenting has allowed many good quality studies to demonstrate the impact sensitive and responsive care has upon child development.(22)

Reflective Parenting:

‘Reflecting Parenting’ is a further theory about how a parent can impact upon a child’s attachment with their caregivers and consequently their overall childhood development. Following on from early work, in 1998 Peter Fonagy described how humans use an understanding of mental states, intentions, thoughts, feelings and beliefs to make sense of and anticipate each other’s actions. This reflective use of making sense of emotional processes is described as ‘mentalisation’ and

demonstrating this ability is termed ‘reflective functioning’.(24) Fonagy believed that a caregiver’s capacity to ‘hold the child in mind’ and understand that they too have their own thoughts and feelings, has been described as crucial in supporting a child in discovering their own internal experiences and the child’s own ability to ‘mentalise’.(25) This in turn can affect the parent-child relationship and the ability to form a secure attachment. This theory is termed ‘Reflective Parenting’. Unlike sensitive and responsive parenting the concept of reflective parenting can only be facilitated if the parents can make sense of their own emotional processes and demonstrate reflective functioning. The concept of reflective parenting and ideas surrounding it are beginning to become more recognised within the UK and are also forming more of a basis for parenting interventions such as the UK based antenatal PEEP courses and building bonds programme in Knowlsey, Merseyside.(25,26)

2.1.2. Piaget’s Cognitive Development Theory

Jean Piaget was a Swiss scholar who felt that intelligence developed in children through a series of processes that children must go through to adapt to their environment.(27)

There were three components to Piaget’s theory; (27)

1. Schemas; the building blocks of knowledge and a way of organising experience, allowing us to understand and predict the world around us.

2. The Developmental Process; Assimilation, fitting the world into new schemas. Equilibrium which leads to disequilibrium, where new experiences occur that cannot be fitted into existing schemas. Finally, accommodation the changing of existing schemas to fit with new experiences. All stages lead to the formation of new schemas.

3. Stages of Development; Piaget believed in four key stages to a child’s development:

Sensorimotor 0-2 Years; As a child reaches 8 months they develop object permanence and this stage focuses on practical interactions with the world through the child’s sensory and motor systems.

Pre-operational Stage 2-7 years; Children begin to interpret the world through images, symbols and language. Although the world itself remains concrete and absolute. The child remains egocentric.

Concrete Operational7-11 years; Children develop cognitive operations. Conservation of numbers, liquids, substance, weight, volume is

understood.

Formal Operational 11-16 years; Children are able to start manipulating ideas, develop abstract reasoning and think logically.

2.1.3. Social Models of Childhood Development

As well as looking specifically at the child-parent relationship as an impacting factor on child development, other theories have emerged in the past 40 years which

explore how the wider environmental factors not only impact upon a child’s cognitive development but also upon the relationships a child forms and therefore their overall development. This includes Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory and Erik Erikson’s stages of psychological development.

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. 1979

Bronfenbrenner, an American developmental psychologist used his ecological systems theory of development to demonstrate how the social environment in which we live can influence all aspects of the child’s development.(28) Bronfenbrenner describes different, nested levels of the environment that can impact upon the child’s development; the microsystem, the mesosystem, the exosystem and the

macrosystem;(29)

The microsystem relates to the immediate environment the child lives in, their home. It also includes the caregivers they interact with on a daily basis. These are their primary caregivers when they are younger and spend most time at home and as they become older those adults in their nursery or child care environment.

Some describe the mesosystem as the interconnections within the microsystem. How parents interact with family and teachers, or the relationships the child forms with its peers and family.

The macrosystem describes the culture in which people live and the wider impact this has upon the child. This includes the relationships the parent themselves have.

The choronsystem demonstrates the changes in these levels of environment over time, as the child ages.

In a paper by Halpern R, on child development, he schematically demonstrates a more modern version of Bronfenbrenner’s theory and how these levels are represented in modern day society; (30)

This theory is an important concept to consider when looking at how parents are being supported with their child’s development. It demonstrates that there are many additional factors that can influence the parent’s daily lives and consequently caregiving abilities, especially when considering the role of the exosystem.

Erik Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development, 1956

Erik Erikson, a German born developmental psychologist, developed a theory highly influenced by Sigmund Freud, in which he identified eight stages of healthy

[image:35.595.131.399.268.449.2]development from infancy to late adulthood. Each stage builds upon the previous stage and he believed that if you did not successfully complete at each stage it was likely to reappear as a problem in the future.(31)

Erikson described two stages the child must past through in the early childhood period, both influenced by their parents. These were as follows; (31)

1. 0-2 years – Hopes: trust vs mistrust;

If the child is well handled and well-loved they will develop trust and security. Badly handled and the child will become mistrustful and insecure.

2. 2-4 years –Will: autonomy vs shame and doubt;

The well parented child will emerge from this stage with autonomy and feel proud rather than ashamed. The child will also learn through the exploration of their surroundings.

Erikson goes on to discuss other stages but these are later on into childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, adulthood and old age periods of life.

Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development are important in demonstrating the impact parents can have upon the psychosocial development of their children.

2.2. Parental Interventions and the Need to Support Parents; The Evidence

Parental interventions can be defined as a variety of services designed to support caregivers with all aspects of parenthood. They aim to improve the natural skills and knowledge of parents in order to benefit the development of their child. In more high income settings parents may have access to many of these information and support services, be it public services, privately run courses or media based interventions which provide all parents with advice, information and support.

I will also look at the evidence surrounding the theory that a parent’s ability to demonstrate these sensitive, responsive and reflective parenting skills is something that occurs naturally. I will explore what affects a parent’s natural parenting abilities to explain why parents require support with their sensitive, responsive and reflective caregiving.

The section will be concluded by exploring the evidence available to support the use of parental interventions, focusing on those available to all parents in the UK as well as the evidence from America and Europe. I will explore the benefit these

interventions have in improving the parent-child relationship and therefore the child’s overall development.

2.2.1. The Importance of Sensitive, Responsive and Reflective Care

Sensitive and Responsive Caregiving

Since Mary Ainsworth first termed the ‘Responsive-Sensitive Theory of Attachment’ many good quality evidence-based research studies have been conducted to show that responsive and sensitive parenting can have benefits for child development. In the UK the theory of providing sensitive and responsive caregiving also forms the basis of many parenting interventions and is a widely recognised theory utilised in many child development settings.

A recent review by The W.H.O stated that;

‘Sensitive and responsive caregiving is a requirement for the healthy

neurophysiological, physical and psychological development of a child. Sensitivity and responsiveness have been identified as key features of caregiving behaviour related to later positive health and development outcomes in young children.’ (4)

child who is physically, intellectually and socially healthy as well as more resilient to the damaging effects of poverty and violence.(4)

Many evidence based studies support this link between sensitive and responsive care with improved child development. Most studies available are of good quality either being case-control studies or observational studies with large cohorts. Most

demonstrate the benefits of sensitive and responsive care in improving cognitive, language and psycho-social development both in the short term and over the course of the child’s life. Two of the studies found whilst evaluating the literature, which have also been highlighted in reviews completed by the W.H.O. are discussed below in more detail as examples of the type of research that has been conducted into sensitive and responsive care. Both studies were chosen as they were longitudinal observational studies with a long follow up period and large cohort of children from mixed backgrounds.

Landry SH, et al demonstrated how responsive care can impact positively upon a child’s cognitive abilities.(32) He observed 283 children at 6 months, 12 months and 24 months as well as at 3 and 4 years. Landry demonstrated that for children whose mothers showed continued responsive parenting they had faster cognitive growth. This was also the case for the 77 preterm children observed within the study.(32) Responsive and sensitive caregiving can also have a positive impact upon a child’s social development.(33,34) One study from the USA found observed 112 mothers with their children at 9 months, 14 months and 22 months.(34) The child’s behaviour was assessed using a variety of models and results showed that those parents who were more responsive had all round better social skills and also higher empathy to maternal distress. As well as improving a child’s social skills and abilities this and other studies have shown that having responsive and sensitive parents can prevent emotional and behavioural problems into the child’s future.(33,34) For preterm children sensitive and responsive parenting has been shown to be particularly important in benefiting long term emotional and behavioural outcomes.(35) Many further studies were found when reviewing the literature which all demonstrates the benefits of responsive and sensitive care, its impact upon

should be supported in their abilities to demonstrate these skills as it can have a significant impact upon their child’s overall development.

Reflective Parenting

Reflective Parenting is a recent popular concept in early child development. Developed from Fonagy’s theory of ‘Reflective Functioning’, which described the human capacity to understand humans’ behaviour, despite underlying mental states and intentions, reflective parenting, is when a mother demonstrates reflective functioning in their caregiving style and has the ability to hold their child in mind. They understand that their child too has their own thoughts and feelings. Research has shown that when a parent has the ability to demonstrate this reflective

functioning it strengthens the child-parent relationship, particularly in terms of attachment.

Prior to reviewing the literature available to support Fonagy’s theory, it is important to understand how reflective functioning is measured. As Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation to measure Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, Pater Fonagy’s initial research team based at the Anna Freud Institute in London have also developed various tools to measure reflective functioning.

there is little validation of these today from outside of this research team. Almost all studies found in this literature review utilise these tools and so the validity of the reflective functioning measurement tools is an important consideration we must take into account when determining the strength of evidence.

Limited research was found to demonstrate the link between reflective functioning and the impact this may have on a child’s development. These studies, as well as the variety of measurement tools created to measure reflective functioning have largely originated from members of Fonagy’s initial research team. Few of the studies found are comparable due to the variety of methods used to measure reflective functioning as well as the use of different tools to measure attachment.(38) I felt it was important to look at these studies in some detail in order to gain a better understanding of how reflective parenting can impact upon child development, especially as the theory is being adapted by child care professionals in Merseyside at this time.

A small scale study by Slade et al, used the PDI to explore a link between 40 expectant mother’s state of mind and positive attachment with their infants at one year.(38) It was concluded that good parental reflective functioning (as measured by the PDI) was linked to the strength of attachment in adult and child as well as the quality of the parental interactions with their child, thus impacting upon that child’s developmental potential.(38) Another study used a cohort of 45 mothers to

understand the link between reflective functioning using the AMBIANCE score and Ainsworth’s strange situation as measurement tools.(39) Those who scored a low AMBIANCE score (high reflective functioning) were significantly more likely to demonstrate a secure attachment with their 10-14 month olds and respectively those with a high AMBIANCE score (low reflective functioning) were likely to

demonstrate a more disorganised attachment.(39) The number of participants in both of these studies was small and it is not clear if any other cofounders may have influenced the results such as socio-economic status, maternal health, age of the mother. Both studies did demonstrate that parents who have good reflective functioning can positively impact upon a child’s attachment.

(demonstrate reflective functioning) plays an important part in their ability to provide care and comfort to a child. These conclusions were drawn from one small scale cohort study of 40 participants.(38) A more recent study of 21 mothers looked into the relationship between a parent’s reflective functioning and their ability to tolerate infant distress. This used a ‘Parenting Reflective Functioning Questionnaire’ to score reflective functioning and a simulated situation to measure parental tolerance.(40) A baby simulator was used to produce a controlled cry which would only cease when the mother demonstrated appropriate soothing as defined by the observer. Those mothers who persisted longer with soothing the child demonstrated higher scores in the questionnaire (higher capacity to demonstrate reflective function).(40) This study suggests that parents who demonstrate higher levels of reflective functioning are more likely to persist with providing responsive and sensitive care and shows a possible link between the two parenting concepts.

Fonagy investigated the role of reflective functioning in ‘buffering’ maternal childhood depravation.(36) Using his original research group Fonagy compared the reflective functioning and consequent infant attachment within groups of mothers who had high levels of deprivation as children to those with low levels of

deprivation. Within the ‘non-deprivation’ group, of those that demonstrated high reflective functioning, 79% had securely attached children. This compared to 42% of those who demonstrated low reflective functioning abilities.(36) Results were even more conclusive in the ‘high levels of deprivation’ group where 100% of those who showed high reflective functioning demonstrated a secure attachment with their child compared to only 6% of those with low reflective functioning scores.(36) The numbers within each cohort was small (the largest group containing 39 participants) however the results are statistically significant when comparing each group and suggest that reflective functioning may have an important role in assisting those with high levels of deprivation as a child, to form a secure attachment with their child.(36) Although completed on a small cohort these results could be of particular interest within Merseyside where childhood deprivation levels are higher than the national average for many decades.

measured, all draw upon similar conclusions in that parents demonstrating good reflective functioning are able to build a secure attachment which can consequently impact upon child development. Fonagy’s exploration of the link between reflective functioning and the ‘buffering’ of social depravation may also have particular significance in places such as Merseyside where many children are growing up in social poverty. Further research would be required to draw to more definitive conclusions.

2.2.2. Barriers to a Parent’s Natural Caregiving Abilities

In this section I will review the evidence which questions whether the ability to demonstrate responsive, sensitive and reflective caregiving is something that occurs naturally. I will explore the factors which research has suggested may influence a parent’s natural caregiving abilities.

There are a number of studies which have concluded that a caregiver’s ability to demonstrate sensitive and responsive caregiving is natural. One study investigating natural caregiving abilities conducted in The Netherlands looked at the caregiving in monozygotic twins. This study aimed to establish whether the genetic make-up of adults influences their natural caregiving responses.(41) It evaluated the responses of 184 twins, both parents and non-parents to a simulated cry, which was mechanically altered to represent different urgencies.(41) Participants were asked to report the response they felt was most appropriate to the cry. Results concluded that genetic factors did in fact influence the sensitivity of their responses with monozygotic twins more likely to demonstrate a similar caregiving response.(41) Although other

environmental factors may have influenced these results, this study concludes that the ability to demonstrate sensitive and responsive caregiving is genetically influenced and natural.

study evaluating anxiety levels in children. In this study it is noted that mothers naturally demonstrated higher reflective functioning abilities than fathers, researchers suggesting that this could be perhaps due to maternal instinct.(42)

If as the research suggests a parents ability to demonstrate responsive, sensitive or reflective parenting is natural, it leads us to question what benefits there are for the ‘universal’ parent who can already demonstrate these skills in having additional support from parenting interventions. It also leads me to questions if parental interventions can improve upon this natural responsive, sensitive and reflective caregiving ability parents have or inversely do not have, or is it something that can be taught? It also leads me to question if there are any influential factors in a parent’s life that can prevent their natural ability to demonstrate sensitive, responsive and reflective caregiving?

One of the first investigations into the theory that a parent’s natural ability can be influenced by external stressors was discussed in Selma Fraiberg’s ‘Ghosts in the Nursery’, 1974.(43) An extract of the paper is shown below;

‘In every nursery there are ghosts. They are the visitors from the

unremembered past of the parents the uninvited guests at the christening.’

(43)

Fraiberg describes that when a child is born, so are the haunted memories of the parents own past and relationships they had with their own parents. It is hypothesised that those parents who had experienced pain and rejection and had consequently reacted to avoid these feelings with denial and isolation, are unable to respond in a positive way to their new-born baby. In her studies this was tested by exploring retrospective histories of both vulnerable and healthy families. It was found that those conflicts observed between current parents and their new-born infant

resembled the parent’s description of their early childhood; the ghosts of their past were appearing in the present.(43)

high association with depression and result in a poor parent-child relationship.(16) These are important factors when considering a parent’s natural caregiving ability, especially in a city like Liverpool where social depravation is high and there are many single families.(16) Some psychologists have suggested that everyday stresses resulting in intrapersonal crises and the modern culture of overloading parents with information, can inhibit a parent’s ability to mentalise and maintain their reflective functioning.(44) These factors, along with the overall stress that having a new-born baby can bring, are all important factors when we consider the needs and role of parenting interventions.

2.2.3. The Benefits of Parenting Interventions

In this section of the review, I will explore the evidence for the use of interventions in supporting parents in their responsive and sensitive caregiving within the context of the UK, Europe and America. I will also review the evidence for the newer parenting interventions, designed to support parents specifically with their reflective parenting.

‘The Abecedarian Project’ has for the past 40 years been looking at the effects of a randomised control trial conducted on 111 children born between 1972 and

1977.(45) Children were randomly assigned to the control group or intervention group where they received intensive, full time educational intervention from infancy to 5 years old. Although this intervention purely targets ‘at risk’ children of North Carolina, United States of America [USA], it is one of the only on-going trials to continually follow its cohort and the effects the parental intervention has had, throughout their adult lives.(45) Therefore its results are worth noting when considering the overall benefits of parenting interventions.

pregnancies. The most interesting results came as part of the follow up at age 35 years where those in the intervention group had fewer measurable risk factors for coronary heart disease (hypertension, obesity and metabolic syndrome).(45) Although there may be many additional factors which have led to these most recent results, it is still interesting to see the possible longitudinal effects a parenting intervention in the first few years of life can have well into adult life.

Like that of ‘The Abecedarian Project’, it was clear that upon completion of this review that the majority of studies investigating the use of parenting interventions are conducted using specific interventions targeted toward a specific cohort of parents. ‘Targeted parents’ are those whose child has a specific disease or behavioural concern. When reviewing the evidence it was hard to isolate research focused on the ‘universal parent’ who didn’t have any risk factors or specific concerns but who just required general parenting support. Only three reports were found to evaluate the more general picture of parenting interventions, one meta-analysis which included 70 studies with various cohorts of targeted and universal caregivers, one literature review and one case-control study.

The meta-analysis drew conclusions about the impact parenting interventions have upon parental sensitivity and responsivity as well as drawing conclusions as to the optimum length of time over which interventions are delivered.(46) It looked at data from over 7,939 participants who were evaluated for sensitivity and 1,503 for responsiveness. Participants of the interventions were from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds and the interventions themselves were targeted to different caregivers and children, or aimed universally at all parents.(46) Researchers

concluded that most interventions were targeted to a specific problem within families and these targeted interventions were more effective at improving responsiveness and sensitivity in parents when compared to the universal interventions. They also concluded that the interventions that had a ‘moderate’ number of sessions, lasting a few weeks or months only, were more effective than shorter interventions or those that lasted many months. One reason thought for this was that those parents with multiple problems lost interest over many months.(46)

included in the meta-analysis. Within the review the cohorts of the studies included children of less than 3 years old and the studies investigated a mixture of targeted and universal interventions. Of these trials 75% demonstrated improved parenting skills, specifically responsiveness and 34% showed that these effects were long-term.(47) These positive results were limited to those studies aimed at targeted populations. There was little evidence for the effect of universal interventions on parental responsivity, although some positive outcomes where discussed such as parents maintaining positive parenting.(47)

Although the meta-analysis concluded that parenting interventions taking place over a moderate length of time were more effective, one recent case-control study looked at the long term impact of a brief 2 hour parenting intervention.(48) 66 mothers and 1 father were randomly assigned to either a 2 hour parenting group intervention, where they were taught general parenting strategies or a control group who were placed on a waiting list for the intervention.(48) Both groups reported back to researchers immediately following the intervention and 6 months post intervention. Those parents who had taken part in the programme reported a decrease in behaviour problems and increased parenting experience compared to the control group.(48)

In terms of sensitive and responsive caregiving, the evidence therefore suggests that parenting interventions can have significant positive impacts upon parents’

caregiving abilities when targeted to a parent’s specific needs. For universal parents who have fewer significant needs compared to those attending targeted interventions and are looking for more general parenting support, the impact parental interventions have on sensitive and responsive care is not as well researched and documented. This therefore leads us to question how universal parents are supported in their sensitive and responsive care if parenting interventions are not always effective.

Evidence was found for one specific parenting intervention with the aim of improving parents’ reflective functioning capacity and reflective parenting skills. Developed at the University of Warwick as part of the Peep Early Educational Partnership [PEEP], antenatal PEEP aims to improve a parent’s reflective capacity.(26) This group have conducted their own small case-control study

the PDI as a tool to measure the outcome, initial results demonstrated that parents’ reflective capacity had improved at the end of programme and that parents were also demonstrating more sensitive parenting, measured using the CARE index.(26) This is not however the programme currently being adopted in Merseyside.

Although there is some evidence to suggest that a person’s parenting ability is natural, with the help of parental interventions or programmes a parent can improve upon their ability to demonstrate responsive, sensitive and reflective caregiving. As ‘The Abecedarian Project’ has shown, targeted interventions can have real long term benefits for future childhood development and into the child’s adult life. The benefits of universal interventions is however not as clear with some research suggesting that parenting interventions can have some positive benefits to improving a parent’s ability to demonstrate sensitive, responsive and reflective caregiving in the universal parent, however at this time the evidence is very limited and not well supported.

2.3. Parental Support in the UK and Merseyside

The key statutory services available to support all parents in England are outlined in the most recent government policy, the ‘2010-2015: Children’s Health Policy’. This policy outlines precisely which government services and support should be available for all parents throughout the UK. Within this evidence-based document there are also a variety of actions that should have been undertaken and implemented by 2015 by the local health authorities and government bodies, these include: (15)

Improving maternity care.

Helping parents to keep their children healthy through the ‘Healthy Child Policy’.

Encourage healthy living through NHS services.

Improve the health visiting service.

Protecting children through immunisation.

Supporting mothers and children with mental health problems.

The ‘Healthy Child Policy’ was introduced in 2005 by the previous Labour government and has been updated at various points over the preceding 5 years. It focuses on how all parents should be supported throughout pregnancy and the first 5 years of a child’s life.(11) It promotes overall healthy wellbeing as well as promoting breastfeeding, immunisation uptake and sensitive caregiving to improve a child’s development. When looking in more detail at the recommendations for improving a child’s development it relies on Health Visitors and children’s centre staff to

encourage parents to read books, use music and engage in various parenting

programmes.(11) It recommends PEEP parenting programmes for universal parents. For those parents with additional needs it recommends programmes such as Triple P and the Family Nurse Partnership. Interestingly, PEEP is not included in the National Academy for Parenting Research’s database as a UK recommended parenting

intervention.(14) This database has been developed since these government policies were produced so the reasons for its exclusion are not clear. This policy was first produced over 10 years ago and its most recent update was 6 years ago so some evidence for the policies and recommendations have changed.

2.3.1. Midwives

The first action outlined by the government policy was that of improving the midwifery service. Their role is outlined as follows,

‘Across the United Kingdom Midwives are key professionals in ensuring that

women have a safe and emotionally satisfying experience during their pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal period.’ (49)

Following the initial publication of this report a review of the midwifery services was undertaken; ‘Midwifery 2020: Delivering expectations’. This report outlines a vision of a cost-effective and quality service to be delivered to new and expectant mothers across the UK by 2020.(49)

All parents in Liverpool will have access to support and advice from Midwives. Although the majority of a Midwife’s role is during the antenatal period, they are also there to support the mother and baby for the first 10 days of life and in some cases throughout the 28 day postnatal period.(50) During this time they are there to provide the mother with important advice regarding parenting as well as

breastfeeding guidance, screening and surveillance of the new born.(49) The encouragement of breastfeeding is a particularly important role as government policies and UK wide campaigns clearly state the evidence to promote breastfeeding as the best form of infant feeding and uptake rates in cities such as Liverpool are extremely low.(6)

2.3.2. Health Visitors

was introduced by the government with the aim of coming into full effect by May 2015.(51) It pledged to commit an extra 4,200 Health Visitors and develop a new more accessible health visiting service. The service it pledged to provide to parents is outlined out-lined below; (51)

1. ‘Your community has a range of services including some Sure Start services and the services families and communities provide for themselves. Health Visitors work to develop these and make sure you know about them.’ 2. ‘Universal services from your Health Visitor and team provide the Healthy

Child Programme to ensure a healthy start for your children and family (for example immunisations, health and development checks, support for parents and access to a range of community services/resources.’

3. ‘Universal plus gives you a rapid response from your Health Visitor team when you need specific expert help, for example with postnatal depression, a sleepless baby, weaning or answering any concerns about parenting.’

4. ‘Universal partnership plus provides ongoing support from your Health Visitor team plus a range of local services working together and with you, to deal with more complex issues over a period of time. These include services from Sure Start Children’s Centres, other community services including charities and where appropriate the Family Nurse Partnership.’

The government have outlined five universal reviews at which point all children in the UK, including those in Liverpool will be seen by the Health Visitor during the first 18 months of a child’s life. This will come into effect when the service

provisions are transferred to the local commissioners in October 2015. They are as follows; (52)

1. During the antenatal period.

2. As a new baby around 10 days old.

3. Between 6-8 weeks.

4. Between 9-12 months.

2.3.3. Sure Start Children’s Centres

Many parenting interventions, support groups and Health Visitor drop in clinics are run from children’s centres in Merseyside. Originally these were opened as Sure Start Children’s Centres, first introduced in 1998 by the then Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown as a support programme for parents from pregnancy to school age. The core free services that the Sure Start Centres across the country must provide include: (53)

Outreach and home visiting.

Support to families and parents.

Primary and community healthcare and advice.

Support for good quality play, learning and childcare experiences for children, both group and home-based.

Support for speech, language and communication.

Support for all children in the community, recognising their differing needs.

Within Liverpool there are 17 core centres as well as 9 additional centres which provide children’s centre services.(54) This means the parents of Liverpool do not need to travel more than a few miles to reach their local centre. In order to provide the core services they hold a series of drop in sessions throughout the week, which have been developed by the fully trained staff in line with child developmental theories which include those to improve attachment and responsive parenting. Across Liverpool each centre offers a similar service to their parents. For example they all offer an opportunity to meet with a Health Visitor and have your child weighed. Some sessions have however been developed specifically to appeal to the parents and their needs within the locality of the centre. Some (Dingle Lane and Wavertree) are also able to utilise nearby council facilities and provide swimming sessions. Kirkby is the only children’s centre in Merseyside which run’s a specific course that promotes ideals of reflective functioning and is currently invitation only for those more vulnerable parents.

In January 2015 it was announced that the Liverpool City Council would be